One midweek morning near the end of September, just after 2am, an angel appeared on the South Shore of Long Island Sound. It grew in size until it was about two miles wide and then it moved down, past Hauppauge and Melville, Garden City and Great Neck, before drifting over the eastern boroughs of New York City. There was a glimmer, just as the first blue light of dawn was appearing, and then it was over. The angel fell earthward and dissolved into hundreds of thousands of winged things. They settled down to the city’s branches and onto its dew-covered lawns.

English radar operators in the late 1940s were the first to see angels like the one that appeared over Long Island last night. On their screens, these structures appeared to be continuous. They were immense, often several miles across. The angels would appear high in the sky, sometimes at 10,000 feet or higher, and were solid enough that they blocked out real targets from the operators.

While the angels were first thought to be caused by meteorological phenomena, scientists had within a decade come to a consensus as to what was actually responsible: large flocks of migrating birds. This was confirmed both statistically, by matching the occurrence of the angels with known migration patterns, and visually, by mounting a telescope on the aerial of a radar tower and observing that birds were indeed present when the angels appeared.

Defense departments and meteorologists have, over the intervening 80 years, figured out how to filter out the ‘noise’ that birds leave on radar screens, to separate angels from incoming aircraft and from late-summer thunderheads. Ornithologists, meanwhile, have learned to use these machine visions of birds to observe migration and to estimate population counts. The culmination of all this work might be BirdCast, a project built by a consortium of U.S. universities, which uses large machine learning models, trained in part on radar images, to offer nightly migration predictions for the lower 50 states.

I was asleep when that September angel arrived, but I got up a few hours later to lead a bird walk for a small group of people in Brooklyn Bridge Park. I’d checked out BirdCast before bed, and then again just as I was headed out the door. According to their model, an estimated 247,800 birds had crossedBrooklyn’s skies the night before, about double the number expected on that date. They’d been flying mostly southeast at altitudes of around 2,000 feet. BirdCast told me to expect Swainson’s Thrushes, a shy ground bird that’s a regular visitor to my park in the autumn. Also black-throated blue warblers, rose-breasted grosbeaks, white-throated sparrows, and great crested flycatchers.

The model makes these specific predictions not from radar images but from decades of data provided by birders. The modern birder is an enthusiastic data collector: on a given day some 13,000 of them across the U.S. complete more than 20,000 digital checklists and submit them to the online platform eBird. eBird’s database contains nearly 1.5 billion bird observations from 820,000 birders. Cornell University’s Macaulay Library holds nearly 55 million photos, videos, and audio recordings of birds, most of them contributed by eBird users. I filled out an eBird checklist that morning, dutifully offering BirdCast the data it needed to both confirm its predictions and to make new ones next year.

When I was asked to join Knowing Machines, I knew I wanted to investigate datasets produced by birders. I wanted to know more about the processes by which the data is gathered and curated and about the human labor that goes into making datasets useful for the specific task of creating and training AI models. I also wanted to understand how these models, built on top of millions of hours of human labor, might be changing the kinds of interactions and understandings that come between people and birds.

How Birders Make Data

“Birder” is an odd word. How does an animal become a verb and then a noun? - Nancy J. Jacobs, Birders of Africa: History of a Network

“Birder” is a catch-all for any person who engages in observing birds for recreational or social reasons. Though there is ample overlap between birders and ornithologists (many birders contribute directly to scientific research; many ornithologists moonlight as birders) the term allows for a useful division between data created by scientists and data created by non-scientists.

Until the late 1800s, observation of birds was mostly facilitated by rifle. Non-scientist birders were typically wealthy landowners, who would submit records (and often specimens) to universities or to organized ornithological clubs. The first coordinated effort to gather data from networks of birders in North America began in 1881, when Wells W. Cooke started the National Bird Phenology Program (NBPP). In its heyday before the Second World War, the program involved 3,000 participants. Before it was officially closed in 1970, nearly 6 million ‘migration observer cards’ had been submitted to the project’s offices in Virginia.

Right as the NBPP was becoming an institution, birders were discovering a transformative tool: portable optics. Binoculars shortened the distance between birders and birds, and made it possible to make fine observations about birds without shooting them. This change made birding possible in urban areas and for people without the means or the temperament to fire a rifle. In 1890, the American ornithologist Florence Merriam published Birds Through an Opera-Glass, considered the first field guide for birders, in which she called binoculars the “inseparable article of a careful observer.” The birder-as-observer was encouraged to take detailed notes about what they saw, including specific field marks and often accompanied by drawings. “The first law of field work,” Merriam wrote, “is exact observation… you will find it much easier to identify birds from your notes than from your memory.”

For much of the 20th century, data about what birders were seeing day-to-day was kept in notebooks. While many birders kept checklists of what they observed, typically only sightings of rare birds were shared, usually in the form of letters to museum curators or to journals such as The Auk or the Linnean Newsletter. In the late 1960s and early 1970s centralized groups were established, responsible for vetting and keeping records or rare bird sightings. The American Birding Association was started in 1969 with the goal of becoming a venue for the exchange of ‘birding information’. The California Bird Records Committee was founded in 1970 and was followed by bird record committees in every state: volunteer-based groups which evaluate and verify records of rare bird sightings. These committees are still active today and remain responsible for vetting observations of a “review list” of birds, typically species considered ‘Code-4’ rarities or higher.

There was one day per year for early birders when their observations of robins and starlings were counted alongside transients and rarities: the Christmas Bird Count. Started in 1900 in Central Park by the ornithologist Frank Chapman and continuing to today, the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) assigns groups of birders the task of tallying all of the birds they can find within a ‘count circle’ of 15 miles in diameter. Numbers are compiled by local chapters of the Audubon Society and reported to the National Audubon Society. Many CBC count circles have more than a century of continuous data collected using a consistent methodology: a tremendously valuable resource for understanding how bird populations have changed, particularly in urban areas. 76,880 birders participated in the 2022 Christmas Bird Count, in 2,621 count circles.

In 1975, the Canadian ornithologist Jacques Larivée began a project to collect and digitize birding checklists from specific localities in Québec. The ÉPOQ Database began with the task of compiling historic and recent sightings into an electronic schema. This format for tabulating observations soon became popular with Quebéc birders, who would complete ÉPOQ observation sheets in place of their usual checklists. This was a watershed moment: birders had always been great producers of data, and ÉPOQ showed that they could be relied on to produce it in machine-friendly ways. Over the next four decades, ÉPOQ participants would produce more than 10 million records. They’d also inspire the creation of a new database platform that would change the habits of birders around the world: eBird.

Like ÉPOQ, eBird provides a uniform data format for birders to record their observations, only at a much larger scale. While the Quebéc project included checklists for more than 5,000 locales in the province, eBird can create birding checklists for any place on the planet. On top of facilitating data collection, eBird facilitates the upload of photographs, video, and audio. Crucially, it connects these media to identifications that are vetted both algorithmically and by eBird’s community of volunteer reviewers.

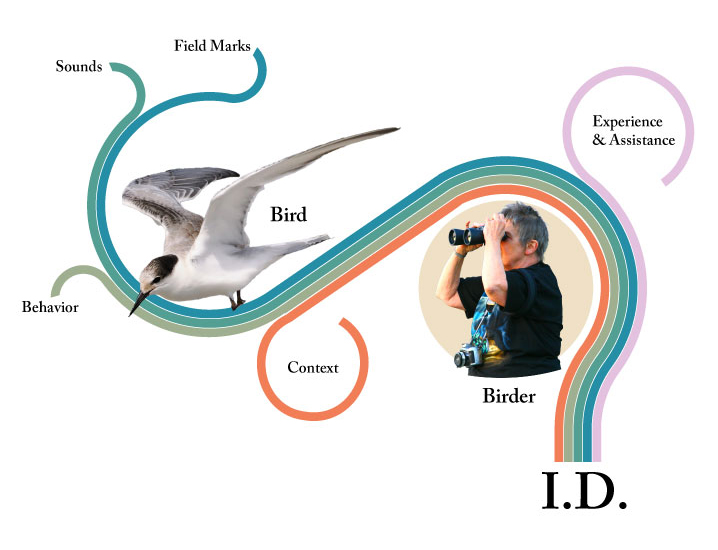

The identification is the fundamental particle of birding data and the primary act of birding. The production of an ID is a synthesis of details gleaned from a bird and its context, as well as the knowledge and experience of the birder.

Every one of the bird data projects discussed so far, from the NBPP to eBird, depends on accurate IDs. Identifications from early birders were vetted on reputation. As the number of birders increased in the 20th century, social mechanisms - the state bird record committees - were developed to validate what were considered to be the most valuable data: identifications of exceptionally rare birds. eBird expanded on the record committee concept and recruited experienced birders to be local reviewers. Today more than 2,000 volunteer eBird reviewers evaluate rare bird reports and checklist outliers (for example observations with larger than expected numbers of birds).

The original purpose for eBird’s extensive verification machinery was to make its data as useful as possible to ornithologists studying population dynamics, by making sure identifications made by its users could be as “trustable” as possible. As more birders began to attach photos and audio to their checklists, eBird’s vetting processes began to produce an extremely useful byproduct: enormous amounts of well-labeled media, perfect grist for machine learning’s mills.

Birds & Machine Learning

The very first machine learning models involving birds, developed in the early 1990s, used sets of several hundreds of images, labeled only with the broad class of objects they contained (bird, bicycle, lamp, bucket, etc). These image sets were often put together by hand by researchers using images from the internet. By 2012, new types of machine learning models were developed that were more hungry for data; instead of training sets numbering in the hundreds, these models needed many thousands of images. The first bird training set aimed at these new models was CUB-200, which contained nearly 12,000 images of birds, with identifications and labels (body parts, colors) provided by crowdsourced workers.

Datasets like CUB-200 are still being produced, largely for use by machine learning researchers working on problems of fine-grained classification. A training set called ‘Birds 525 Species’ is updated annually and contains (at the time of writing) nearly 90,000 images, gathered through internet searches for species names. Birds also appear in more wide-ranging wildlife image sets, such as those produced by camera traps, and in larger general purpose image datasets such as LAION-5B. As evidenced in the opening discussion, birds can also be present in images from weather radar, and colonies of birds are detectable from satellite images, though no pre-prepared training sets seem to be available to the public.

Bird sound training sets are also readily available. One popular dataset, often used for models designed to detect birds, consists of 6,620 audio clips from remote monitoring equipment in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Another audio training set called Warblr is composed of 10,000 ten-second recordings made with cell phones in the UK, birds songs intermixed with human conversation and all manner of urban noise.

Preparation of these datasets only peripherally involves birders. Birders are, in many cases, the source of the photographs in the sets, but they play no role in verifying IDs or in confirming the performance of resulting models. These datasets are largely used to produce models that can demonstrate success at a specific category of task (fine-grained classification) rather than models that can reliably identify birds in the field.

Today’s most successful bird-focused machine learning projects, specifically Merlin Photo ID and Merlin Sound ID, don’t use pre-prepared training sets like the ones outlined above. Instead, these projects are embedded in eBird’s well-established architectures of data collection and moderation. These projects work with photographs and sound recordings, which eBird users submit and verify by the thousands every day.

This is not to say that Merlin’s training sets are merely exhaust from eBird. For both ImageID and SoundID, teams of expert volunteers use bespoke interfaces to label media in the specific ways that are useful to the training of models. One key task is to draw bounding boxes around the body of the bird or the waveform of its call. This process is particularly challenging for audio, in which a single recording might include dozens of calls, which may in some cases be layered on top of one another.

Birders not only generate Merlin’s training datasets; they also refine, augment and quality-control them. Might birders then expect to be able to access this data? I was surprised when I began investigating Merlin’s dataset-making practices that there was only a single public data release associated with the project. The NABirds dataset was released in 2020 and contains nearly 30,000 well-labeled images of the 600 most common species of North American birds. Meant as a kind of update to CUB-200, NABirds was built with the participation of experienced birders and ornithologists, who verified and labeled each image in a similar fashion to how photographs are processed for ImageID. Though it might be viewed as a kind of subset of Merlin ImageID’s training data, it is by no means as large or as comprehensive.

No training data from Merlin SoundID has been released. Neither SoundID nor ImageID have released trained models for use or investigation by the public (BirdNet, a bird call detection project operated out of Cornell but separate from Merlin, has published a model for general use)

Investigating datasets is a critical tool to understanding how AI models come to “know” the world. Knowing what a model’s training set does or doesn’t contain helps us to comprehend both its capabilities and its limitations. The Merlin app has been downloaded more than 12 million times. Today, there are more than three million people out in the world whose experience of nature is mediated by Merlin, and many more who are using AI tools like it. These people are being guided by the particular ways that models have learned to know birds, and pulled by these tools’ very real desires for more and more data.

Birding’s Three Body Problem

To become a birder is to be changed by birds. One week, you’re ordering binoculars and the next, you’re waking up before dawn, you’re changing your route to work to pass by a tulip tree that’s come into bloom, you’re looking up in the sky as much as you're looking at your phone. Watch them for long enough, and birds will begin to rewire your brain, to tune it to their own instincts and desires.

Birders change birds, too. Consider the Jocotoco Antpitta, a South American bird that was, until the 20th century, largely unknown to science. Small and ground-dwelling and very, very shy, antpittas are - or were - a kind of ultimate challenge for birders. That changed when Ecuadorians realized antpittas could be trained - and that people could be charged a tidy sum for a guaranteed sighting. Travel to the cloud forests of Ecuador today, and you can see an antpitta named Mike exchange a few Instagram-perfect moments of its presence for a handful of worms.

On a more quotidian level, birders change birds simply by being around them. This can be witnessed in its extreme nearly every day in Central Park, where charismatic birds like owls are rarely without an entourage of camera-touting fans who click and capture every flight and feast and defecation. Even in smaller groups and in quieter parks, people insert themselves into the energetic equations of birds, affecting how they forage, feed, and sleep.

This two-way relationship between birds and birders has been mediated by tools. Rifles, binoculars, field guides, cameras, cell phones - all of these things have modified the ways that birders go about their birding business. All of these tools act in one or more ways on birding’s central challenge: identification. They bring birds closer, they slow them down, they make them more readable and easier to find.

AI models are rapidly becoming birders’ “inseparable article”. Beginners are very often encouraged to install apps like Merlin on their phones before they even raise their binoculars to the sky for the first time. For good reason: there’s no denying the fact that these tools make it easier for people to learn the basics of birding. AI models, though, are in one critical way different from the birding tools of the past. Where a 12-gauge shotgun or a pair of Swarovski binoculars asks nothing from their users, an AI model does: it wants data.

Merlin Sound ID is an app powered by a model, fed training data produced by a community, vetted by volunteers, funded by a university, guided by very specific research goals. If we bundle all of that up into a single entity, Merlin’s desire is to get better at identifying the recorded calls of birds. To do that, it needs to hear more sound recordings from different places with different sonic conditions: it needs more training data. The way to get more training data is to turn more birders into sound recordists, to change their behavior such that they think of recording sound with the same frequency at which they might take a photograph.

BirdCast, the radar migration model, wants birders to make eBird checklists, because these checklists can be used to verify its predictions - and to make new ones for the following year. Merlin also wants birders to use eBird and make checklists, because checklists are a way for it to ground-truth its IDs. As more and more birders make these tools a part of their practice, more and more birders are being conditioned to prioritize specific ways of experiencing wildlife. However subtly, they’re being taught to privilege enumeration over observation, to see nature as a thing to be inventoried.

While models are changing birders, birders are also changing models. The biases of birders – the places they tend to go, the species they prefer to find – trickle up into models and influence the way they “know” the world. The kinds of birders that use mobile apps are overwhelmingly male and white and live in the Global North. It’s no surprise then that an AI model trained on data from these birders might detect a dozen species on an autumn morning in Brooklyn, yet “hear” exactly none on a spring afternoon in Lagos.

Birds and models also push and pull at each other, albeit in less obvious ways. Some birds confound models by being hard to see or hear; others confuse them by mimicking the way other species look and sound. Birds break data schemata by having four sexes, or by hybridizing, or by generally being more complicated than a machine might like. Models, as they become more ubiquitous, will influence conservation policy. Remote sensing stations fitted with sound and vision models are already being deployed to monitor habitats, passing along their pre-trained biases and blind spots to the decisions they inform.

It’s October now, and while the birds are still arriving on their nightly flights, the cast of characters is changing. There are still Swainson’s thrushes and black-throated blue warblers, joined now by golden-crowned kinglets and dark-eyed juncos. In a few weeks, the fall migration’s late shift will arrive: woodcocks, nuthatches, chickadees and sparrows. Many of these birds will overwinter here; they’ll stay long enough to be counted in this year’s Christmas Bird Count, the 123rd.

What the CBC data will tell us, along with BirdCasts’ migratorial counts and eBird’s checklists, is that very many of these birds are facing bleak futures. According to an Audubon study published this year, a full two-thirds of bird species in North America are at increasing risk of extinction from climate change. Many of the birds that migrate through New York in the fall breed in boreal forests, which are warming at double the speed of the rest of the planet. Audubon’s predictions put these birds at the greatest risk.

Just a few minutes into my walk in September, we found a Swainson’s Thrush perched on a low branch in the shade. Swainson’s thrushes are birds that can effortlessly go unseen. They like to skulk in the underbrush, their russet-brown backs and speckled breasts making them hard to spot in the shadows. Swainson’s thrushes become even more inconspicuous in the fall, because they blend in so well with the fallen leaves. Our Brooklyn bird took a full minute for everyone to see, even though it was only a few meters away.

These autumn thrushes are even harder to find for AI models, for several reasons. Swainon’s Thrushes are (mostly) silent in the fall, and shadowy forests make for difficult photography. Fewer birders are outside, carrying fewer phones with fewer apps: less than half the number of eBird users filed checklists in the U.S. on the first Monday of October than on the first Monday of May. The models will have better luck in the spring, when warmer days will hear the Swainson’s song - a climbing spiral of flute-like notes - ring through parks and forests across the continent.

According to Audubon’s forecasts, the Swainson’s thrush stands to lose 37% of its range with a 1.5º temperature change – 73% with a 3º shift. To survive, the birds will have to relocate to new places with unfamiliar habitats. How they will react to this change is an open question: one that will be answered by new generations of early-rising birders, carrying binoculars and consulting AI models.

Appendix: Birds Of The AI Resistance

1.The Many-Voiced

Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos)

Young male mockingbirds learn to mimic the sounds of other birds around them: the ones in my neighborhood park have wide sonic repertoires that include cardinals, gulls, and red-tailed hawks (plus the occasional car alarm). Some mockingbirds have been observed to perform more than 400 different ‘songs’. Their mimicry is good enough that it can fool sound identification models. This mucks with models in two ways: by adding IDs of birds that weren’t actually there and by underrepresenting IDs of actual mockingbirds.

2.The Nearly Invisible

Black Rail (Laterallus jamaicensis)

The black rail is perhaps the most enigmatic bird in North America. A wetland dweller, it spends most of its life hidden in dense reed beds. Black rails do make noise, but only at night, when birders are unlikely to be out in a marsh. All of this adds up to a bird with a long history of resisting datafication. “You go back to the very beginning [of ornithology in North America]; they didn’t know anything about this bird,” says Bryan Watts, the director of the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. “You come up to the present; we still don’t know anything about this bird. It’s because of how secretive it is.” The Black Rail may be present in AI identification datasets but is very rarely observed (and even more rarely photographed) by the users of the models.

3.The Easily Mistaken

Philadelphia Vireo (Vireo philadelphicus)

The Philadelphia Vireo looks a lot like a different vireo, and it sounds almost exactly like two others. The rarest of all four, the “Philly Vireo” is notoriously undercounted by humans who fail to pick up on the subtle differences between it and its look- and sound-alikes. Merlin Sound ID seems to have the opposite tendency: it seems to hallucinate Philly Vireos even when they’re not around. Enough so that eBird reviewers I spoke with in NYC were in the habit of rejecting any report of the bird where Merlin was used to arrive at the ID.

4.The High-Arcing Mariners

Bermuda Petrel (Pterodroma cahow)

About 3% of all birds live most of their lives at sea, coming on land only to nest and raise their young. People might catch glimpses of these species from the decks or cruise ships or on overnight pelagic boat tours that ferry gravol-dosed birders out past continental shelves. Most of their lives, though, are spent very much out of reach of telephoto lenses and sound recorders - the open sea is off the AI grid.

5.The 26%

The continent of Africa is home to more than a quarter of the world’s birds, but it is dramatically under-represented in bird-focused AI models. None of the continent’s species are supported by Merlin Sound ID. According to the model’s makers, two things regulate whether a region is supported: availability of at least 100 high quality sound recordings per species and the presence of “enough expert annotators” in the region. The red-billed quelea, which ranges across much of the continent, is considered to be the most numerous bird on the planet. While it can flock in numbers higher than 10 million individuals, the species only has 16 eBird checklists with recorded audio. This exposes the main bias in citizen-contributed bird datasets: data comes from the species birders usually see, in the places where birders usually go.

With assistance from Hamsini Sridharan.

October 2023

Birds Through A Knowing Glass

If Not Them, Us

Odd Ducks: The Hybrid Logics of Machine Learning in Fine-Grained Wildlife Classification